The five years or so has seen the rise of several new directors from France who’ve made quite a splash with their Hollywood debuts. There’s Alejandro Aja with Haute Tension (or Switchblade Romance/High Tension) who brought back the late 70’s early 80’s sensibilities of what constitutes a good slasher, exploitation film. Then there’s Jean-Francois Richet whose 2005 remake of John Carpenter’s early classic, Assault on Precinct 13 surprised quite a bit in the industry. Neither film made too much in terms of box-office, but they did show that a new wave of genre directors may not be coming out of the US but from France of all places. Another name to add to this list is Florent Siri and his first major Hollywood project Hostage shows that he has the style and skills to make it in Hollywood.

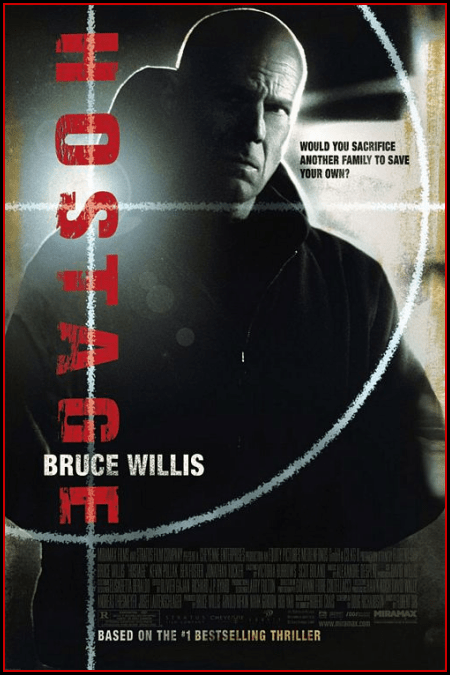

Hostage is another Bruce Willis vehicle that was adapted by Doug Richardson (wrote the screenplay for Die Hard 2) from Robert Crais’ novel. Hostage is a very good thriller with a unique twist to the hostage-theme. Willis’ character is a burn-out ex-L.A. SWAT prime hostage negotiator whose last major case quickly ended up in the death of suspect and hostages. We next see him as chief of police of a small, Northern California community where low-crime is the norm. We soon find out that his peace of mind and guilt from his last case may have eased since taking this new job, but his family life has suffered as a consequence. All of the peace and tranquility is quickly shattered as a trio of local teen hoodlums break into the opulent home of one Walter Smith (played by Kevin Pollak). What is originally an attempt to steal one of the Smith’s expensive rides turn into a hostage situation as mistakes after mistakes are made by the teens.

From this moment on Hostage would’ve turned into a by-the-numbers hostage thriller, but Richardson’s screenplay ratchets things up by forcing Willis’ character back into the negotiator’s role as shadowy character who remain hooded and faceless throughout the film kidnap his wife and daughter. It would seem that these individuals want something from the Smith’s home and would kill Willis’ character’s family to achieve their goals. The situation does get a bit convoluted at times and the final reel of the film ends just too nicely after what everyone goes through the first two-third’s of the film.

The character development in the film were done well enough to give each individual a specific motivation and enough backstory to explain why they ended up in the situation they’ve gotten themselves into. Willis’ performance in Hostage was actually one of better ones in the last couple years. The weariness he gives off during the film was more due to his character’s state of mind rather than Willis phoning in his performance. I would dare say that his role as Chief of Police Jeff Talley was his best in the last five years or so. The other performance that stands out has to be Ben Foster as the teen sociopath Mars. Foster’s performance straddles the line between being comedic and over-the-top and could’ve landed on either side. What we get instead is one creepy individual who almost becomes the boogeyman of the film. In fact, the last twenty minutes of Hostage makes Mars into a slasher-film type character who can’t seem to die.

The real star of the film has to be Florent Siri’s direction and sense of style. From the very first frame all the way to the last, Siri gives Hostage the classic 70’s and 80’s Italian giallo look and feel. Siri’s use of bright primary colors in conjuction with the earthy, desaturated look of the film reminds me of some of the best work of Argento, Bava and Fulci. In particular, Siri’s film owes alot of its look to films such as Tenebrae, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, and The Psychic. Certain scenes, especially the penultimate climax in the Smith home, take on an almost dreamlike quality. Siri’s homage to the classic gialli even gives Hostage some sequences that would comfortably fit in a 70’s slasher film.

Florent Siri’s Hostage is not a perfect film and at times its increasing tension without any form of release can be unbearable to some people, but it succeeds well enough as a thriller. It also shows that Siri knows his craft well and instead of mimicking and cloning scenes from the gialli he’s fond of, he emulates and adds his own brushstrokes. The film is not for everyone and some people may find the story convoluted if not dull at times, but for me the film works well overall. Siri is one director that people should keep an eye on.