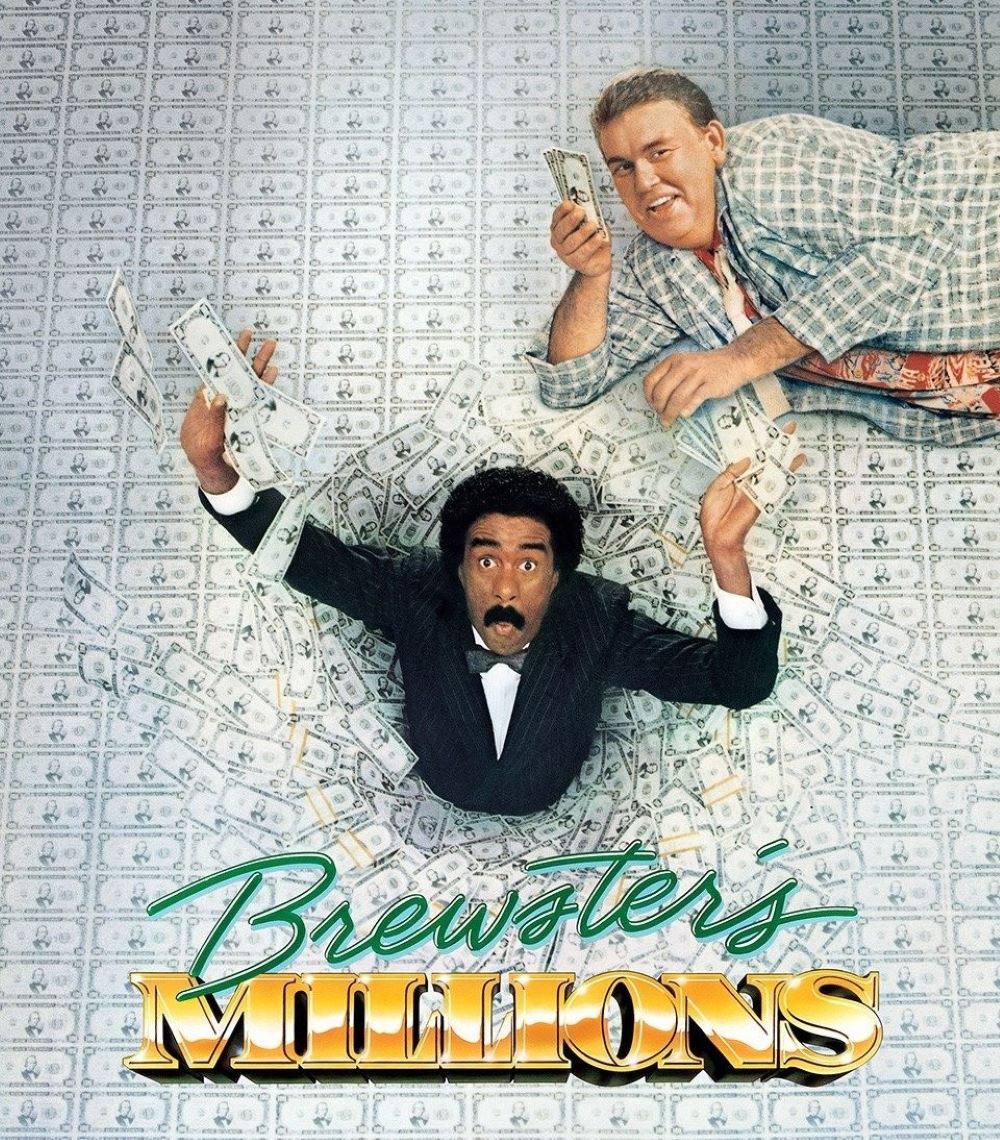

Walter Hill’s Brewster’s Millions (1985) isn’t a perfect movie by any stretch, but it’s the kind of film that sneaks up on you. It may not be sharp enough to qualify as great satire or consistent enough to hit every comedic note, but it has an undeniable charm that pulls you in regardless. It’s loud, uneven, and often ridiculous, yet few comedies from the 1980s are as weirdly entertaining when they’re firing on all cylinders. For many movie fans, it’s that quintessential “guilty pleasure”—a film you know has problems, but that somehow feels impossible to turn off once it starts. And in many ways, that’s exactly where Brewster’s Millions finds its lasting appeal.

The setup alone is too fun to resist. Richard Pryor stars as Montgomery Brewster, a minor league baseball pitcher who unexpectedly inherits the opportunity of a lifetime—to claim a $300 million fortune from a distant relative. The catch? Before he can get it, he has to spend $30 million in 30 days under a bizarre set of conditions that make financial ruin easier said than done. He can’t give the money away, can’t destroy it, can’t buy assets or investments that retain value, and can’t tell anyone why he’s doing it. Fail, and he gets nothing. Succeed, and he becomes one of the richest men alive. It’s the sort of gleefully absurd premise that could only have come from Hollywood in the 1980s, and it’s immediately clear that the film wants audiences to sit back, grab some popcorn, and watch Pryor tear through cash in increasingly funny and desperate ways.

Richard Pryor is, without doubt, the heart and soul of the movie. He imbues Montgomery Brewster with equal parts manic energy and human frustration, giving the character a real emotional arc beneath all the comic spectacle. Pryor’s talent for blending humor with exasperation makes Brewster’s predicament believable, even when it’s insane. Watching him scramble to lose money while the world keeps rewarding him is strangely satisfying. Pryor understood how to play ordinary men caught in extraordinary circumstances, and that quality grounds the film when it could have easily spiraled into total silliness. In scenes where he loses his patience with accountants, schemes wild spending sprees, or watches his good intentions backfire, Pryor’s comic timing keeps the chaos enjoyable.

John Candy adds another layer of charm as Brewster’s best friend and teammate, Spike Nolan. Candy brings warmth, loyalty, and that unmistakable good-heartedness that made him one of the decade’s most beloved comedic actors. The chemistry between Pryor and Candy keeps the film buoyant even through its weaker stretches. Their friendship defines the film’s tone—it’s loose, goofy, and full of bro-ish camaraderie. Without Candy’s infectious energy, the movie’s more hollow comedic beats might have hit the floor with a thud. Together, they create a dynamic that feels real, even inside a premise that’s totally absurd.

As a director, Walter Hill feels like an odd fit for this kind of broad comedy, but that’s part of what makes Brewster’s Millions interesting. Hill, better known for tough, kinetic action films like The Warriors and 48 Hrs., approaches this farce with a surprising amount of structure and visual precision. The film looks slicker and sharper than most comedies of its kind, which gives the excess on-screen an unintentionally epic flair. Hill’s direction keeps the story moving, and though he’s not naturally a comedic filmmaker, his grounded style adds a peculiar edge to all the craziness. It’s chaos with discipline—an aesthetic that somehow works in the movie’s favor.

Still, Brewster’s Millions can’t quite escape its shortcomings. The pacing is uneven, especially in the middle, where the film loses some steam as Brewster cycles through increasingly repetitive spending gimmicks. The story flirts with satire but rarely commits, brushing up against deeper commentary on wealth, politics, and capitalism before retreating to the comfort of broad comedy. The “Vote None of the Above” subplot, where Brewster’s money-wasting political campaign taps into voter cynicism, is one of the smartest parts of the film—but it’s introduced and resolved too quickly to leave a mark. And while the movie is full of lively energy, not every gag lands; a few supporting performances veer into caricature, and some jokes feel very much of their time.

Yet these flaws are partly what make Brewster’s Millions such a delightful guilty pleasure. It’s the cinematic equivalent of junk food—high on calories, low on nutritional value, but deeply enjoyable all the same. Pryor’s constant exasperation, the sheer absurdity of trying to “waste” money legally, and the exaggerated set pieces (like the overblown parties or his failed attempts to lose at gambling) make for irresistible entertainment. Even when the humor dips into predictable territory, the concept keeps pulling you back in. There’s a giddy satisfaction in watching Brewster try—and fail—to lose money, especially because the universe just won’t let him.

The romance subplot with Lonette McKee’s character, Angela Drake, adds just enough heart to balance the absurdity. McKee gives a grounded, intelligent performance that prevents the love story from feeling tacked on, even if it never fully takes center stage. Her presence keeps Brewster tethered to some kind of reality, and the moral through-line—learning that not everything valuable can be bought—lands gently rather than preachily. It’s not profound, but it fits the breezy tone perfectly.

As a comedy of excess, Brewster’s Millions is very much a product of its time. The slick suits, the gaudy parties, the blind faith in wealth, and the Reagan-era optimism about money’s moral neutrality all ooze from every frame. That time-capsule quality is part of its modern appeal. Watching it today, you can’t help but smile at how on-the-nose it feels—a movie from the “greed is good” decade that accidentally ends up mocking the very mindset it sprang from. It’s self-aware only in flashes, but those flashes are enough to make you recognize the movie’s satirical edge hiding beneath its loud surface.

In the end, that’s what makes Brewster’s Millions endure as a lovable guilty pleasure. It has flaws you can’t ignore—uneven pacing, scattershot tone, underdeveloped ideas—but none of them outweigh its charm. Pryor’s comic genius makes even the weakest joke land better than it should. Candy’s warmth keeps the film light. And Hill’s straightforward direction infuses the lunacy with just enough realism to make it believable. The result is a movie that’s too silly to take seriously but too fun to dismiss. You watch it, laugh at its audacity, shake your head at the logic gaps, and yet somehow come away smiling.

Brewster’s Millions may not be a comedy classic, but it’s easy to see why people keep revisiting it. It’s comfort food cinema—lighthearted, clumsy, and endlessly watchable. And like all the best guilty pleasures, it doesn’t need to be perfect to make you happy. Sometimes, seeing Richard Pryor outsmart the meaning of money for two hours is more than enough.

Previous Guilty Pleasures

- Half-Baked

- Save The Last Dance

- Every Rose Has Its Thorns

- The Jeremy Kyle Show

- Invasion USA

- The Golden Child

- Final Destination 2

- Paparazzi

- The Principal

- The Substitute

- Terror In The Family

- Pandorum

- Lambada

- Fear

- Cocktail

- Keep Off The Grass

- Girls, Girls, Girls

- Class

- Tart

- King Kong vs. Godzilla

- Hawk the Slayer

- Battle Beyond the Stars

- Meridian

- Walk of Shame

- From Justin To Kelly

- Project Greenlight

- Sex Decoy: Love Stings

- Swimfan

- On the Line

- Wolfen

- Hail Caesar!

- It’s So Cold In The D

- In the Mix

- Healed By Grace

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Legend of Billie Jean

- Death Wish

- Shipping Wars

- Ghost Whisperer

- Parking Wars

- The Dead Are After Me

- Harper’s Island

- The Resurrection of Gavin Stone

- Paranormal State

- Utopia

- Bar Rescue

- The Powers of Matthew Star

- Spiker

- Heavenly Bodies

- Maid in Manhattan

- Rage and Honor

- Saved By The Bell 3. 21 “No Hope With Dope”

- Happy Gilmore

- Solarbabies

- The Dawn of Correction

- Once You Understand

- The Voyeurs

- Robot Jox

- Teen Wolf

- The Running Man

- Double Dragon

- Backtrack

- Julie and Jack

- Karate Warrior

- Invaders From Mars

- Cloverfield

- Aerobicide

- Blood Harvest

- Shocking Dark

- Face The Truth

- Submerged

- The Canyons

- Days of Thunder

- Van Helsing

- The Night Comes for Us

- Code of Silence

- Captain Ron

- Armageddon

- Kate’s Secret

- Point Break

- The Replacements

- The Shadow

- Meteor

- Last Action Hero

- Attack of the Killer Tomatoes

- The Horror at 37,000 Feet

- The ‘Burbs

- Lifeforce

- Highschool of the Dead

- Ice Station Zebra

- No One Lives