VGM Entry 68: Final Fantasy VI

(Thanks to Tish at FFShrine for the banner)

Square released quite a number of games for the Super Nintendo, but everyone looked forward above all else to their annual blockbuster, appearing in the latter half of the year, from 1993 until 1995. Secret of Mana was the first of these. Final Fantasy VI was the second.

There is only one logical place to begin a discussion of the music of Final Fantasy VI.

And that would be at the beginning. Final Fantasy VI did not begin like other games. Sure, it was by no means the first to fade out on the title screen and play through an introduction to the plot, but this was different in a lot of respects. It provided barely any background to the story. Ok, there was a devastating war 1000 years ago in which the destructive art of “magic” was lost, and an emerging industrial revolution is beginning to recover remnants of that past. That’s all you directly get. The rest plays out more like a movie. You get hints and clues to what’s going on–a new face here, a key term there–but you’re left curious rather than informed. The intro to this game doesn’t set the plot; it sets the mood. (The revised English translation tragically lost sight of this, such that the original SNES “Final Fantasy III” is really the only port of the game worth playing.)

Nobuo Uematsu’s music went hand in hand with this approach. There is no opening anthem–no catchy piece to hum along to. The sinister organ, the harp-like transition, the windy sound effects, and ultimately the opening credit music all flow from one point to the next, breaking only for the sake of the cinematic experience, not because a particular track is over or the next scene has new “bgm”. Final Fantasy VI had perhaps the first really cinematic introduction for a video game.

It might be argued that Nobuo Uematsu revolutionized the use of music in video games from the very opening sequence, but nothing made this more apparent than the events at the Jidoor Opera House, where an odd twist in the plot leads the cast of heroes to become involved in a backstage operation during a musical performance. Not only does the opera take place in the backdrop as you work your way through the mission, but as part of the plot device the heroine Celes takes on the lead female roll in the show. Events transition back and forth between action behind the scenes and the live show, and part of the outcome is determined by your ability, as a player, to regurgitate Celes’ lines from the script.

The video I’ve linked here includes the first two songs in a four-part performance. What makes this sequence so important for the history of gaming music is that Nobuo Uematsu’s amazing score plays a direct role in the plot and gameplay. While the simulated pseudo-vocals might sound silly in hindsight, this was also a real first in gaming music in its day. Square’s sound team might not have possessed the technology to incorporate real words, but nothing prevented them from displaying them as part of the script. As an odd consequence, one of the first video games to make extensive use of lyrics had no vocals.

Uematsu’s third major accomplishment, the indisputable quality of his score aside, was to completely derail the limits of acceptable song length. Granted Commodore 64 artists had been busting out 6-8 minute epics back in the mid-80s, the standard by and large still remained firmly below the 3 minute mark. If we take the opera as a single piece (it’s divided into four tracks), Final Fantasy VI had three songs that pushed 20 minutes.

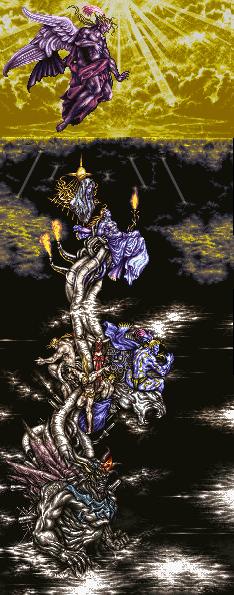

“Dancing Mad” probably remains today the longest final battle music ever written, with the original ost version clocking in at 17 minutes and 39 seconds. This might seem excessive if you haven’t played the game, but within its context nothing less could have possibly sufficed. Kefka was pretty much the greatest video game villain of all time (Luca Blight from Suikoden II might surpass him), and Final Fantasy VI might have had the most apocalyptic plot in the series. Sure, series fans had saved the world from imminent destruction five times before and plenty more since, but Zeromus, Exdeath, they were just icons of evil. In Final Fantasy VI, Square’s obsession with mass destruction finally found a human face. Kefka’s psychopathy was something you could buy into. He was entirely capable of emotion even as he slipped progressively further into insanity. He just attached no moral value to life. Where enemies before and since sought to destroy the world for destruction’s sake, Kefka was in it for the experience of the ultimate tragedy. For once it actually made sense for a final boss to let the heroes creep up on him; the whole agenda would have been pointless if no one was there to experience it with him.

Both visually and musically, the final battle of Final Fantasy VI was beautiful. Nothing else–certainly no 1-2 minute fight theme–would have been appropriate in the context of the story.