“One missing piece doesn’t make you any less whole.” — Ava Fremont

The Silent Hour is the kind of mid-budget thriller that used to quietly fill up Friday night multiplex lineups, and there’s something refreshing about that. It is not reinventing the genre, but it does just enough with its premise of hearing loss, a deaf witness, and a sealed-off apartment block to feel engaging instead of disposable. When it leans into that sensory angle and the physical geography of the building, it clicks; when it falls back on stock corrupt-cop beats, you can feel the air go out of the room a little.

The setup is straightforward: Boston detective Frank Shaw (Joel Kinnaman) is struggling with permanent hearing loss after an on-the-job accident, trying to find a way back onto the force and into his own life. He is brought in because he knows some sign language and is asked to help take the statement of Ava Fremont (Sandra Mae Frank), a deaf photographer who has video evidence of a brutal gang murder. Once Frank leaves her run-down apartment building, he realizes he forgot his phone, heads back, and walks straight into a hit team sent to silence Ava; the rest of the film traps them inside the almost-condemned complex with a crew of killers who, crucially, they often cannot hear coming.

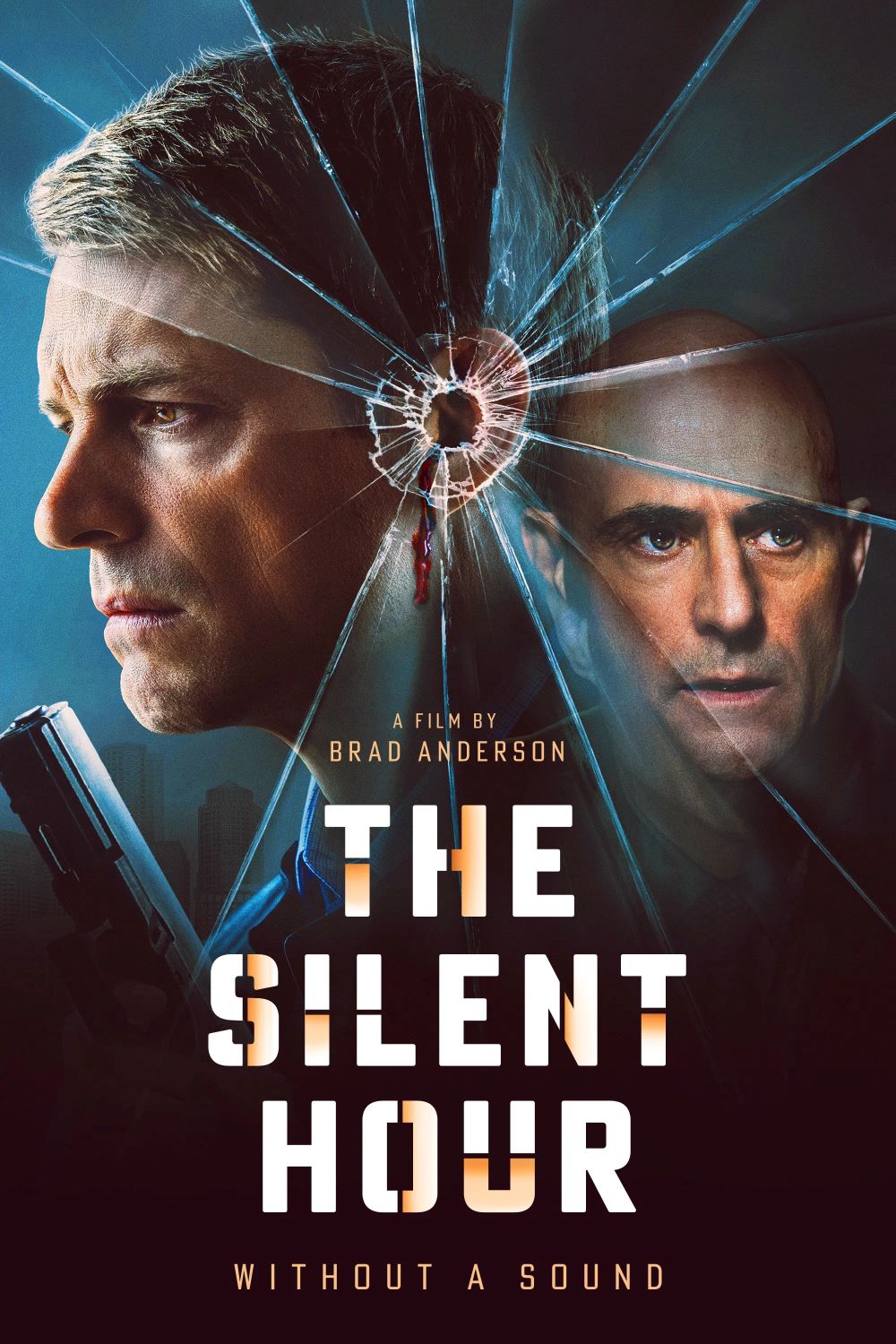

Director Brad Anderson has always had a knack for tense, contained spaces, and you can feel the same instincts here that powered films like Session 9 and Transsiberian, even if The Silent Hour is more conventional. The apartment block is shot as a grim, half-abandoned maze: flickering lights, long hallways, and just enough remaining tenants to complicate any hope of a clean escape. Anderson stages several sequences as slow, creeping cat-and-mouse instead of wall-to-wall gunfire, which fits the “you can’t hear the danger” concept nicely and gives the movie a more claustrophobic vibe than the plot synopsis might suggest.

Where the film genuinely distinguishes itself is in how it uses sound—or sometimes refuses to use it. Scenes that shift into Frank’s perspective often dampen or distort the audio, letting the score fall away so small vibrations, visual cues, and body language carry the tension, while Ava’s point of view goes further, dropping into near-total silence and forcing the audience to scan frames the way she would. It is not as radical as something like A Quiet Place, but it is effective, and the sound department clearly understands that “absence” can be as expressive as any bombastic action mix.

Kinnaman slides comfortably into this kind of bruised, low-key action role, and here he plays Frank as a guy permanently half a step behind the world around him, frustrated but not wallowing. The script gives him some predictable beats—guilt, self-destructive drinking, a shot at redemption—but Kinnaman sells the physical awkwardness of someone relearning how to move and work while not fully trusting his own body. Sandra Mae Frank is the movie’s secret weapon, though; as Ava, she never reads as a passive victim, and there is a practical, almost sardonic edge to the way she navigates the situation that helps keep the film from turning mawkish about disability.

The dynamic between Frank and Ava is also where the film finds its heart, even if it is pretty lightly sketched. Their communication is messy at first—his sign language is rusty and limited, hers is fast and precise—but that awkwardness becomes part of the tension, because a misread sign or delayed understanding can get people killed in this environment. As they settle into a rough rhythm, the movie quietly nudges Frank toward accepting that his hearing loss is not just a temporary obstacle but a permanent part of who he is now, and Ava is allowed to be more than a symbolic “guide” through that, with her own fears and bad decisions hanging over her.

On the flip side, the actual crime plot is about as standard as they come. The villains are corrupt cops cleaning up a messy murder, and if you have seen more than a couple of thrillers, you will probably guess who is dirty long before the script “reveals” it. There are a few half-hearted attempts at moral compromise and temptation—a hefty bribe, old loyalties—especially around Frank’s former partner Doug Slater (Mark Strong), but the story never digs into systemic rot or moral ambiguity in any meaningful way; it just uses corruption as a convenient engine to keep the bullets and double-crosses coming.

Structurally, the film works best as a series of mini-scenarios inside the building rather than as a twisty conspiracy. You get sequences where Frank and Ava navigate dark stairwells while trying to stay ahead of men they can feel but not hear, tense face-offs in cramped apartments with panicked tenants, and a few well-staged bursts of violence that remind you this is still a pretty nasty situation. The climax leans into fire, chaos, and one last push for survival, and while the resolution lands exactly where you’d expect, the final quieter beats give the characters a bit of closure that feels earned rather than tacked on.

Performance-wise, the supporting cast does its job without stealing the movie. Mekhi Phifer and Mark Strong bring some veteran presence as fellow cops circling around Frank, and even when the writing nudges them toward archetype, they at least feel like people who have known each other for years rather than walking plot devices. The henchmen are more one-note, essentially “the guys with guns” hunting through the building, but the film leans on their physicality and menace instead of trying to give everyone a tragic backstory, which is probably the right call for a lean thriller like this.

If there is a frustration here, it is mostly about missed potential. The core hook—two people with hearing loss trying to survive in a sound-dependent cat-and-mouse game—is strong enough that you can imagine a slightly sharper script pushing much harder on point of view, communication breakdown, and the way the police institution treats disability. Instead, The Silent Hour uses those elements as flavoring around a very familiar skeleton, resulting in a movie that is solid and sometimes gripping but rarely surprising.

Taken on its own terms, though, The Silent Hour is a tight, competently staged thriller that understands how to milk a confined space and an offbeat sensory angle for suspense. The running time is under two hours, the pacing stays brisk, and there are enough well-executed set pieces and committed performances to make it an easy recommendation if you are in the mood for a darker, low-key action night. It will not stick with you the way the very best of Brad Anderson’s work does, but as a late-night watch with the lights down and the volume doing most of the heavy lifting, it gets the job done.