2005’s The Call of Cthulhu is several stories in one.

In a mental hospital, an apparent madman (Matt Foyer) talks to his psychiatrist (John Bolen) about the death of his uncle, a professor who had similarly gone made during his final days. The man’s uncle was obsessed with evidence of a worldwide cult who worshipped an ancient being, perhaps named Cthulhu and perhaps sleeping somewhere in the ocean. When his uncle died, the man received all of his research. The files detailed the discovery of a cult in Louisiana, with the added caveat that the man who discovered the cult himself died under mysterious circumstances. Later a boat is found floating at sea and the records within suggest that the boat’s crew met a fearsome creature on a dark and stormy night. As soon becomes clear, the price for investigating Cthulhu is losing one’s own sanity. Once a researcher realizes that Cthulhu and the Old Ones are real and that the universe really is beyond understanding or human control, insanity inevitably follows.

H.P. Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu was originally published in 1928 and it remains Lovecraft’s best-known work. It’s often cited as the start of the Cthulhu mythos, though Lovecraft had hinted at Cthulhu’s existence in previous stories. Lovecraft was a prolific correspondent who kept in contact with other pulp writers and who allowed them to add to the Cthulhu mythos. As a result, it seems as if writing a Cthulhu story has become a rite of passage for many aspiring horror writers. (Even Stephen King has written a few.) H.P. Lovecraft may have not been a household name when he died but Cthulhu ensured his immortality.

Why has Cthulhu had the impact that it has? I think the answer is right there in the story. As the characters come to realize, Cthulhu is beyond understanding and, because it cannot be understood, it cannot be defeated. Cthulhu and the other Great Old Ones are beyond humanity’s traditional concepts of good and evil. Whereas other monsters can be defined and often defeated by what they want, Cthulhu is beyond such concerns. Not even the members of his cult really seem to be sure just what exactly it is that they’re going to gain from their worship.

Cthulhu represents powerlessness of humanity in the face of a cold and uncaring universe. Cthulhu represents chaos. There is no way to fight Cthulhu but, because Cthulhu is such an enigma, intellectually curious humans (and Lovecraft’s protagonists often were academics) find themselves drawn to him. But the minute one starts to research Cthulhu, they are inevitably drawn to their destruction. The same is probably true of people who specifically read short stories and watch movies about Cthulhu. We’re all doomed. I hope this hasn’t ruined your Wednesday.

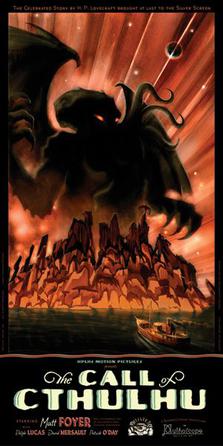

The Call of Cthulhu was long-considered to be unfilmable but, in 2005, director Andrew Leman proved the skeptics worng. Realizing that The Call of Cthulhu was the epitome of 1920s horror, Leman made the clever decision to adopt the story in the style of a 20s-silent film. The black-and-white cinematography is gorgeous, the title cards perfectly capture the melodramatic tone of 20s cinema (and they also help with the fact that Lovecraft’s dialogue doesn’t always sound natural when spoken aloud), and the largely practical effects capture the haunting horror of Lovecraft’s vision. The moment when the boat’s crew meets Cthulhu at sea is especially well done, with the stop-motion effects proving themselves to be far more effective than any CGI could be. The end result is a film pays tribute to Lovecraft while also bringing to life the mystery of Cthulhu.