(Thank you shout-out to my friend Mark for recommending this film!)

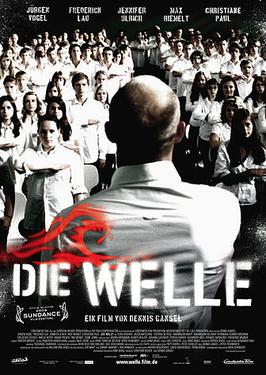

The 2008 German film, The Wave, opens with history teacher and water polo coach Rainer Wenger (Jurgen Vogel), driving to class while listening to the Ramones’s Rock and Roll High School.

Rainer may be a middle-aged authority figure who expects his water polo players to train hard and to always put winning above everything but he still considers himself to be a punk rock rebel, an anarchist who brags about all of the protests that he was involved with. Rainer is upset when he learns that he has been assigned to teach a week-long course on “autocracy.” He very much wanted to teach a class on “anarchy” but that class has been assigned to the most uptight and autocratic teacher in the school. Already feeling resentful, Rainer becomes even more annoyed when it becomes clear that the majority of his students are convinced that there will never be another dictatorship in Germany.

Rainer decides to show them how easily fascism can take root by becoming a dictator in his classroom. Rainer orders the students to call him “Mr. Wegner.” He tells them to all wear the same uniform of jeans and a white shirt to class and when his most intelligent student shows up for class wearing a red blouse because she “doesn’t look good in white,” Rainer refuses to call on her when she raises her hand in class. Mr. Wegner institutes assigned seating, controlling who can sit with who. Everyone is required to stand up if they want to speak. When one student says that he doesn’t want to do any of this, Rainer kicks him and his friends out of class. All three of them eventually return.

Rainer’s experiment works a bit too well. The students come to love being a part of the movement that they come to call The Wave. The Wave ostracizes outsiders, both in school and outside. The Wave covers the town in graffiti, announcing their presence. The Wave doesn’t really have a set goal but the students in Rainer’s class are now obsessed and fanatically loyal to it. One former outcast, Tim (Frederick Lau), becomes so devoted to the cause that he even starts carrying a gun to school so he can defend the other members of The Wave….

If this all sounds familiar, it’s because The Wave is based on the novelization of the American television special of the same name. The German version of The Wave, however, is far more cynical than the American version. Whereas the American version features Bruce Davison as a mild-mannered but always well-intentioned liberal who realizes that his classroom experiment had gone too far, the German version features a teacher who, despite his self-proclaimed radicalism, comes to enjoy the ego boost of being a dictator in the classroom. (Rainer, of course, puts his fascism in superficial left-wing terms, railing against the corporations that make expensive clothing and the individualism that he claims was keeping his class from coming together.) Rainer becomes willfully blind to what he has created. And if the American version of The Wave featured students who eventually learned a lesson and voluntarily walked away from the group they had previous celebrate, the German version presents students who are not willing to abandon their cause, even when their leader tells them that it is time to move on. If the American version featured students who were just play-acting as fascists, the German version features students who go from being blithely unconcerned with the prospect of dictatorship to being the enthusiastic foot soldiers in a cause that has no reason to exist outside of controlling the lives and thoughts of others. If The American version ended with hope for the future, the German version ends with tragedy.

It’s a dark film. Some might claim that The Wave is not a horror film but, by the end of the movie, Rainer’s students have become as relentless and destructive as the zombies from a Romero film or the fanatics who often showed up in Wes Craven’s pre-Scream movies. It takes just one week to transform them from being ordinary teenagers to being the shock troops in a directionless but destructive revolution. They are asked to surrender their individuality and their power to think for themselves and all of them do so without much hesitation, with the desire to belong suddenly superseding everything else about which they claimed to care. Consider this well-acted and disturbing film to be an example of the horror of everyday life.