“What kind of American are you?” — Unnamed ultranationalist militant

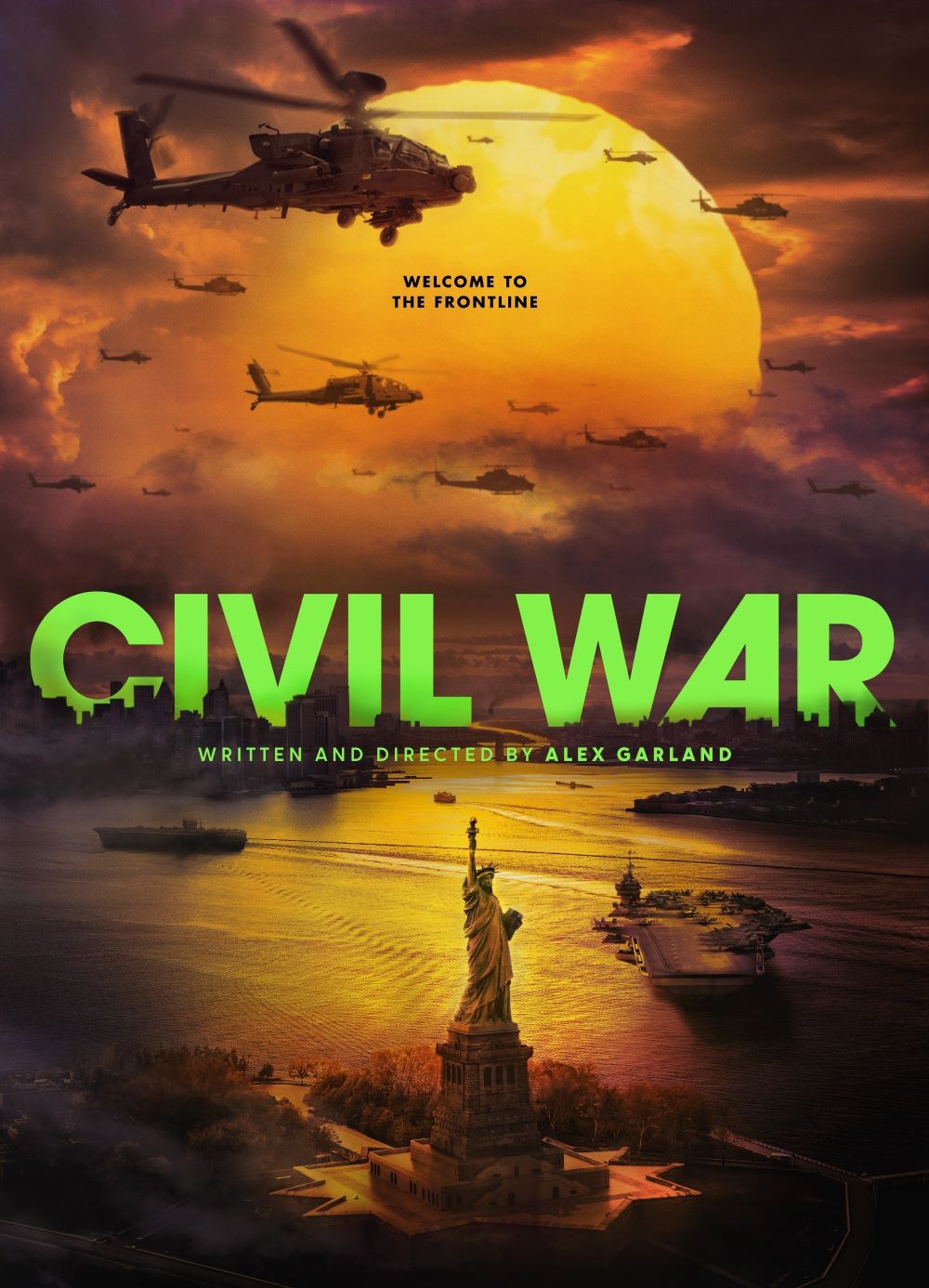

Alex Garland’s Civil War is the kind of movie that feels both uncomfortably close to reality and strangely abstract at the same time, like a nightmare built out of today’s headlines but deliberately smudged at the edges. It plays less like a political thesis and more like a road movie through a country that has already gone past the point of no return, seen through the eyes of people whose job is to look at horror and keep pressing the shutter anyway.

Garland frames the story around war journalists traveling from New York to Washington, D.C., hoping to reach the President before rebel forces do, and that simple premise gives the film a clear spine even when the politics around it stay fuzzy. Kirsten Dunst’s Lee, a veteran photographer, and Cailee Spaeny’s Jessie, a young aspiring shooter, are paired with Wagner Moura’s adrenaline-chasing reporter Joel and Stephen McKinley Henderson’s weary old-timer Sammy, forming a sort of dysfunctional road-trip family driving straight into hell. The setup is classic “last assignment” territory, but the context—an America shattered by an authoritarian third-term president and secessionist forces from places like Texas and California—is what makes the film play like speculative non-fiction rather than pure sci-fi. That Texas-California alliance as the Western Forces stands out as such strange bedfellows, two states about as diametrically opposed as you can get politically and culturally, which subtly hints at just how monstrous the president must be to drive them into the same camp against a common enemy.

The plot itself is pretty straightforward once you strip away the political expectations people bring in. The group moves from one pocket of chaos to another, crossing a patchwork United States where some areas still look almost normal while others are full-on war zones. The tension ramps as they get closer to Charlottesville and then D.C., eventually embedding with Western Forces as they push toward the capital. Along the way, the journalists encounter a series of vignettes—mass graves, roadside militias, bombed-out towns—that feel intentionally episodic, like flipping through the front page of a dozen different conflicts and realizing they all share the same language of fear and dehumanization.

Performance-wise, Dunst is the emotional anchor, playing Lee with a kind of hollowed-out professionalism that feels earned rather than performative. Her character is someone who has seen too many wars abroad and now finds herself documenting one at home, and Dunst sells that numbness without turning Lee into a complete emotional void. Spaeny’s Jessie, meanwhile, is the mirror opposite: all raw nerves and hungry ambition, constantly pushing closer to danger for the shot, until that drive becomes its own kind of addiction. Their dynamic—mentor vs. rookie, caution vs. thrill—gives the movie a human arc to track even when the bigger national stakes remain frustratingly vague.

The supporting cast makes the most of their moments. Moura brings a reckless charm to Joel, someone who clearly gets off on the chaos even as he understands the risks, while Henderson’s Sammy has that lived-in, old-school journalist vibe that makes his presence feel instantly comforting. Nick Offerman’s president shows up mostly as an image and a voice—an isolated leader giving delusional addresses about “victories” and “loyalty” while the country burns—which fits Garland’s choice to keep power distant and almost abstract. And then there’s Jesse Plemons in a late, unnerving scene as a soldier interrogating the group with the question “What kind of American are you?”, a moment that pulls the film’s subtext about nationalism and dehumanization right up to the surface.

Visually, Civil War is stunning and deeply unpleasant in the way it should be. Garland and his team lean heavily into realism: grounded battle scenes, chaotic firefights, and that disorienting sense of being in the middle of something huge and unknowable, with the camera clinging to the journalists as they scramble for cover or line up a shot. The film often uses shallow depth of field, throwing backgrounds into blur so explosions and tracers feel like ghostly streaks behind the tight focus on a face or a camera lens, which reinforces how narrow the characters’ survival focus has become. Sound design is equally aggressive—gunfire, drones, and explosions hit hard in a theater, and Garland doesn’t shy away from making violence both terrifying and, in a way, disturbingly exhilarating.

That’s one of the film’s more interesting, and arguably more uncomfortable, tensions: it’s overtly anti-war in its messaging, but it also understands that war, on a visceral level, can feel like a rush. Several characters clearly chase that feeling, and the film doesn’t let them—or the audience—off the hook for enjoying the adrenaline that comes from life-or-death stakes. There are moments where the action almost tips into “too cool” territory, but Garland usually undercuts this with the emotional fallout afterward, making it clear the cost of those images and thrills is paid in trauma and numbness.

Where Civil War is really going to divide people is in its politics—or more accurately, its refusal to spell them out. The film never fully explains how this United States got here or exactly what the sides are fighting over, beyond hints of authoritarian overreach and regional alliances like the Texas-California Western Forces. You get breadcrumbs: a third-term president who dissolved norms, references to an “Antifa massacre,” and presidential rhetoric that echoes real-world strongman language, but Garland refuses to plant a big obvious flag that says, “This is about X side being right or wrong.”

Depending on what you want from the movie, that choice either feels smartly universal or frustratingly evasive. On one hand, treating the conflict like a kind of Rorschach test lets viewers project their own anxieties onto the screen; it becomes a story about any country pushed too far by polarization, propaganda, and the normalization of violence. On the other, the vagueness around ideologies can come across as sidestepping tough specifics, especially in today’s charged climate, where audiences might crave a bolder stance on division and power.

To the film’s credit, its focus is very clearly on the experience of war, not the policy debates that preceded it. The journalists are not neutral robots; they have opinions, fears, and moments of moral conflict, but their professional instinct is to document first, analyze later, and that’s the lens the film adopts as well. You see how the job warps them: Lee’s exhaustion, Jessie’s desensitization, Joel’s thrill-seeking, Sammy’s weary sense of duty. In that sense, Civil War feels as much like an ode and a critique of war journalism as it does a warning about domestic collapse.

That said, the character work will not land equally for everyone. The emphasis on spectacle and raw incident sometimes leaves less room for layered personal depth, with figures beyond the leads feeling more archetypal than fully fleshed out. Even Lee and Jessie are shaped primarily by their roles in the chaos rather than extensive personal histories, which suits Garland’s lean, immersive style but might leave some wanting more nuance.

The last act, set during the assault on Washington and the White House, is where the film fully commits to being a war movie rather than a political allegory. The battle is staged with a mix of big, chaotic action and small, intimate beats: journalists diving behind columns, soldiers shouting directions, Jessie pushing closer to get the shot even as bullets hit inches away. It’s brutal and propulsive, driving home the film’s bleak thesis: once violence is normalized, legitimacy and process vanish, replaced by whoever has the most guns in the room.

Is Civil War perfect? No. It is at times overdetermined in its imagery and underdetermined in its world-building, and the decision to keep the “why” of the war so foggy will absolutely alienate viewers who wanted a sharper, more pointed statement about the current American moment. But it is also undeniably gripping, technically impressive, and thematically rich enough to spark real conversation about violence, media, and how far a society can bend before it breaks. As a piece of speculative near-future filmmaking, it lands somewhere between warning and reflection: not saying “this will happen,” but asking whether a country this polarized and numb to cruelty should be so confident that it won’t.