Two of the best films released last year dealt with troubled artists.

The End of the Tour opens in 2008, with a writer David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg) getting a call that the famous and acclaimed author, David Foster Wallace (Jason Segel), has committed suicide. After learning of the tragedy, Lipsky remembers a few days that he spent interviewing Wallace 12 years earlier. Wallace had just published his best known work, Infinite Jest. At the time, Lipsky himself was a struggling writer and he approached Wallace with a combination of admiration and professional envy. Lipsky hoped that, by interviewing Wallace, he could somehow discover the intangible quality that separates a great writer from a merely good one.

Almost the entire film is made up of Lipsky’s conversations with Wallace. We watch as both the somewhat reclusive Wallace (who seems both bemused and, at times, annoyed with his sudden fame) warms up to Lipsky and as Lipsky forces himself to admit that Wallace might actually be a genius. There are a few conflicts, mostly coming from the contrast between the withdrawn Wallace and the much more verbose Lipsky. Lipsky’s editor (Ron Livingston) continually pressures him to ask Wallace about rumors that Wallace was once a drug addict. But, for the most part, it’s a rather low-key film, one that’s more interested in exploring ideas than melodrama. It’s also a perfect example of what can be accomplished by a great director and two actors who are totally committed to their roles. Jason Segel, especially, gives the performance of his career so far.

The shadow of Wallace’s suicide hangs over the entire film. Throughout their conversation, Wallace drops hints about his own history with depression. Much as Lipsky must have done after Wallace’s suicide, we find ourselves looking for clues to explain his death. But ultimately, Wallace remains a fascinating enigma in both life and death.

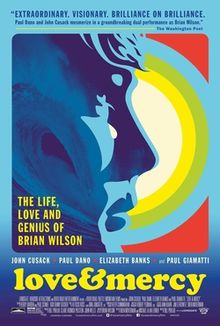

Love & Mercy (dir by Bill Pohland)

Love & Mercy opens with Cadillac saleswoman Melinda Ledbetter (Elizabeth Banks) selling a car to a polite but nervous man (John Cusack). The man sits in the car with her and rambles for a bit, mentioning that his brother has recently died. Soon, the man’s doctor, Eugene Landy (Paul Giamatti), shows up and Melinda learns that the man is Brian Wilson, a musician and songwriter who is famous for co-founding The Beach Boys. After having a nervous breakdown decades before, Brian is now a recluse. He and Melinda start a tentative relationship and Melinda quickly discovers that Brian is literally being held prisoner by the manipulative Dr. Landy.

Throughout the film, we are presented with flashbacks to the 1960s and we watch as a young Brian (Paul Dano) deals with both the pressures of fame and his own relationship with his tyrannical father (who, in an interesting parallel to Brian’s later relationship with Landy, is also Brian’s manager). As Brian struggles to maintain his grip on reality, he obsesses on creating “the greatest album ever.”

Love & Mercy is an enormously affecting story about both the isolation of genius and the redeeming power of love. Whether he’s played by Cusack or Dano, Brian Wilson remains a fascinating and tragic figure. It’s hard to say whether Cusack or Dano gives the better performance. Indeed, they both seem to be so perfectly in sync with each other that you never doubt that the character played by Paul Dano will eventually grow up to become the character played by John Cusack. Both of them do some of the best work of their careers in Love & Mercy.