Did you know that up until the year 1936, if a child was born to unwed parents, it was common practice to actually put the word “illegitimate” on that child’s birth certificate? As you all know, I am perhaps the biggest history nerd in the world and, while I knew that there was once a huge stigma associated with being born outside of marriage, I did not know just how institutionalized that stigma was.

Did you know that up until the year 1936, if a child was born to unwed parents, it was common practice to actually put the word “illegitimate” on that child’s birth certificate? As you all know, I am perhaps the biggest history nerd in the world and, while I knew that there was once a huge stigma associated with being born outside of marriage, I did not know just how institutionalized that stigma was.

I’m also proud to say that my home state of Texas — the state that all the yankees love to bitch about — was the first state to ban the use of the word “illegitimate” on birth certificates. This was largely due to the efforts of Edna Gladney, an early advocate for the rights of children. Along with starting a home for orphans and abandoned children in Ft. Worth, Edna also started one of the country’s first day care centers for the children of working mothers.

That’s right — there was a time when day care was itself a revolutionary concept.

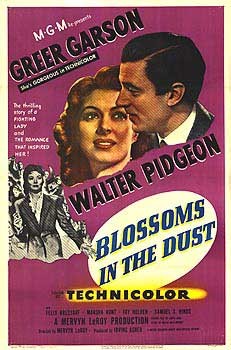

I have TCM to thank for my knowledge of Edna Gladney, largely because TCM broadcast a 1941 biopic called Blossoms in The Dust. According to Wikipedia, the film was a highly fictionalized look at Edna’s life but, to be honest, I would have guessed that just from watching the movie. While Blossoms In The Dust gets the important things right (and it deserves a lot of credit for sympathetically dealing with the cultural stigma of being born to unwed parents at a time when it was an even more controversial subject that it is today), it’s also full of scenes that are pure Hollywood.

In real life, Edna knew firsthand about the challenges faced by children of unwed parents because she was one herself. Apparently, at the time, that was going too far for even a relatively progressive film like Blossoms In The Dust so, in Blossoms, Edna (played by Greer Garson) is given an adopted sister named Charlotte (Marsha Hunt). When the parents of Charlotte’s fiancée discover that she was born outside of marriage, they refuse to allow Charlotte to marry their son. In response, Charlotte commits suicide.

In real life, Edna was born in Wisconsin but, following the death of her stepfather, moved to Ft. Worth to stay with relatives. Edna was 18 at the time and eventually met and married a local businessman named Sam Gladney. In Blossoms in The Dust, Edna is already an adult when she first meets Sam (played by Walter Pidgeon, who played Greer Garson’s husband in a number of films) and they meet in Wisconsin. It’s only after Charlotte dies that Edna marries Sam and it’s only after they’re married that Edna moves to Texas. Whereas the real life Edna had relatives in Texas, the film’s Edna is literally a stranger in a strange land.

That said, the film is actually rather kind to my home state. The film spend a lot of time contrasting the judgmental snobs up north with the more straight-forward people who Edna meets after she moves to Ft. Worth and it’s occasionally fun to watch. (Of course, I would probably feel differently if I was from Wisconsin.)

Blossoms In The Dust was nominated for best picture but it lost to How Green Was My Valley. Greer Garson was nominated for best actress but she lost to Joan Fontaine in Suspicion. However, just one year later, Garson would win an Oscar for her performance in the 1942 best picture winner, Mrs. Miniver. Incidentally, her husband in that film was played by none other than Walter Pidgeon.

Ultimately, Blossoms in the Dust is typical of the type of movies that you tend to come across while watching films that were nominated for best picture. Some best picture nominees were great. Some were terrible. But the majority of them were like Blossoms in the Dust, well-made, respectable, and just a little bit bland. Blossoms in the Dust is not bad but it’s also not particularly memorable. If, like me, you’re a student of history and social mores, Blossoms in the Dust has some historical interest but, when taken as a piece of cinema, it’s easy to understand why it’s one of the more forgotten best picture nominees.