Since the Oscars are approaching, I thought I would devote February to continuing my never-ending quest to watch and review every single film nominated for best picture!

With that in mind, I recently watched the 1928 film In Old Arizona. In Old Arizona is a bit of an oddity in Oscar history. Even though it is considered to have been a best picture nominee, it was never officially nominated. In fact, in 1929, there were no official nominees. Instead, the Academy simply announced the names of the winners. The winners were selected by a small committee of judges. The committee’s intentions are particularly obvious when you notice that not one film won more than one Oscar in 1929. At a time when the industry was struggling to make the transition from silent film to the talkies, the 1929 Oscars were all about spreading the wealth and reassuring everyone that they were doing worthwhile work. In Old Arizona‘s star, Warner Baxter, was named the year’s best actor while Broadway Melody was declared to have been the best picture.

(At that year’s Oscar ceremony, the second in the Academy’s history, the awards were reportedly handed out in 10 minutes and nobody gave an acceptance speech. If this all seems strange when compared to the annual extravaganza that we all know and love, consider that Louis B. Mayer originally formed the Academy in order to give the studio bosses the upper hand in a labor dispute. The awards were largely an afterthought.)

Years later, Oscar historians came across the notes of the committee’s meeting. The notes listed every other film and performer that the committee considered. Before settling on Broadway Melody, the committee apparently considered In Old Arizona. For that reason, In Old Arizona is considered to have been nominated for best picture of the year.

If it seems like I’ve spent a bit more time than necessary discussing the history behind the 1929 Oscars, that’s because In Old Arizona isn’t that interesting of a film. It was a huge box office success in 1929 and it was an undeniable influence on almost every Western that followed but seen today, it’s an extremely creaky film. Influential or not, there’s not a scene, character, or performance in In Old Arizona that hasn’t been done better by another western.

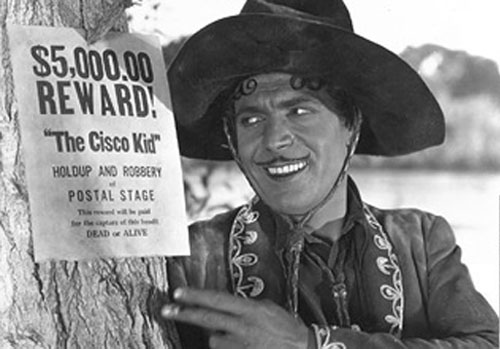

Based on a story by O. Henry, In Old Arizona tells the story of a bandit named The Cisco Kid (Warner Baxter). Cisco may be an outlaw but he’s also a nice guy who enjoys a good laugh and occasionally sings a song while riding his horse across the Arizona landscape. (California and Utah stood in for Arizona.) The Cisco Kid may rob stagecoaches but he always does it with a smile. Besides, he only needs the money so that he can give gifts to his girlfriend, Tonia (Dorothy Burgess). What the Cisco Kid doesn’t know is that Tonia is bored and frustrated by his frequent absences and she has been cheating on him. Then she’s approached by Sgt. Mickey Dunn (Edmund Lowe), the big dumb lug who has been ordered to bring the Kid in (dead or alive, of course). Will Tonia betrayed the Kid?

If you’re watching In Old Arizona and hoping to be entertained, you’ll probably be disappointed. Almost everything about this film has aged terribly. Watching the film, it’s obvious that none of the actors had quite figured out how to adapt to the sound era and, as such, all of the performances were very theatrical and overdone. Probably the easiest to take is Edmund Lowe, who at least managed to deliver his lines without screeching. Sadly, the same cannot be said of Dorothy Burgess. As for Warner Baxter, he may have won an Oscar for playing the Cisco Kid but that doesn’t make his acting any easier to take.

And yet, if you’re a history nerd like me, In Old Arizona is worth watching because it really is a time capsule of the era in which it was made. In Old Arizona was not only the first Western to ever receive an Oscar. This was also the first all-talking, all-sound picture. Watching it today, without that knowledge, you might be tempted to wonder why the film lingers so long over seemingly mundane details, like horses walking down a street, the ticking of a clock, a baby crying, or a church bell ringing. But, if you know the film’s significance, it’s fun to try to put yourself in the shoes of someone watching In Old Arizona in 1929 and, for the first time, realizing that film could not just a visual medium but one of sound as well. For some members of that 1929 audience, In Old Arizona was probably the first time they ever heard the sound of a horse galloping across the landscape.

(I have to admit that, as a student of American history, I couldn’t help but get excited when one of the characters mentioned President McKinley. McKinley may be forgotten today but audiences in 1929 would not only remember McKinley but also his tragic assassination. By mentioning that McKinley was President, In Old Arizona not only reminded audiences that it was taking in the past but that it was also taking place during what would have been considered a more innocent time. Much as how later movies would use John F. Kennedy as a nostalgic symbol of a more idealistic time, In Old Arizona uses William McKinley.)

In Old Arizona is no longer a particularly entertaining film but, as a historical artifact, it is absolutely fascinating.