“The future is not a straight line. It is filled with many crossroads. There must be a future that we can choose for ourselves.” — Kiyoko

Akira is a landmark anime film that has left an indelible mark on both the medium and popular culture, widely regarded as a masterpiece blending dystopian cyberpunk aesthetics with potent social and political themes. Directed by Katsuhiro Otomo and released in 1988, it is an adaptation of Otomo’s own manga of the same name, adding layers of depth from its source material. The film remains a touchstone for its groundbreaking animation, complex narrative, and deep thematic explorations that resonate decades after its release.

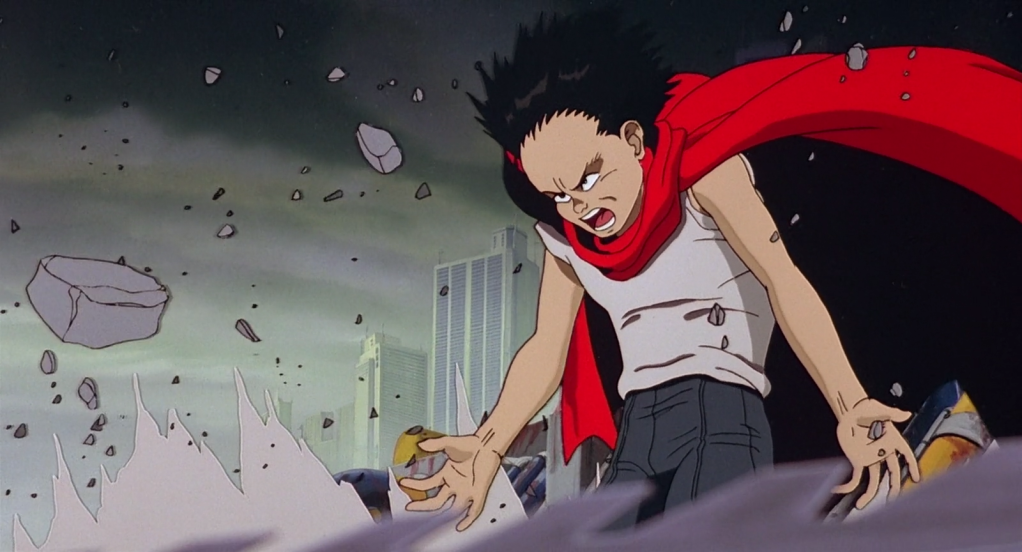

At its surface, Akira tells the story of a post-apocalyptic Neo-Tokyo, a city ravaged by past destruction and on the brink of chaos again due to psychic powers unleashed unexpectedly on its streets. The narrative centers around two childhood friends caught in this upheaval: Kaneda, a rebellious gang leader, and Tetsuo, whose sudden acquisition of devastating psychic abilities leads to uncontrollable transformation and societal breakdown. This conflict draws viewers into a gripping tale of friendship, power, and loss.

Beneath the action-packed plot lies a rich tapestry of themes. One of the most striking is the exploration of loss of humanity through power. Tetsuo’s descent into madness as his psychic abilities spiral beyond his control serves as a visceral metaphor for how absolute power corrupts and alienates. The transformation he undergoes, from a troubled youth into a monstrous entity, dramatizes the fear of losing oneself when faced with forces that cannot be tamed. Meanwhile, the other characters and factions, including the military and resistance groups, depict varying responses to such disruptive power, from authoritarian control to emergent heroism among society’s outcasts and delinquents, emphasizing resilience in adversity.

Akira’s setting is crucial to understanding its impact. Unlike other dystopian sci-fi that glamorizes technology, Neo-Tokyo is raw and unpolished—a place of grime, corruption, and social decay. This lack of fetishization makes the depicted world more relatable and unsettling, reflecting post-World War II anxieties in Japan. The narrative draws clear analogies between the trauma of nuclear devastation and the cyclic nature of destruction and rebirth. The film and manga respectively underline how societies can be dehumanized by catastrophe yet still harbor hope for renewal and change.

The adolescent characters also embody a universal coming-of-age struggle, where uncertainties of identity, power, and responsibility mirror Japan’s own postwar societal shifts. Tetsuo’s monstrous growth and Kaneda’s protective yet rebellious nature capture the complex emotions of fear, resentment, and desire for control, making the story as much about internal battles as external ones. This allegorical layer brings timeless relevance, inviting viewers to reflect on personal and collective growth in times of turmoil.

From a technical and artistic standpoint, Akira set new standards for animation. The film’s fluid motion, attention to detail, and atmospheric world-building were revolutionary for the time and still hold up remarkably well. Otomo’s insistence on lip-syncing dialogue and meticulous frames elevated the cinematic experience far beyond typical anime productions of the 1980s. Its high-budget production values and painstaking artistry make every scene visually immersive, from frenetic gang fights to apocalyptic psychic battles.

One of the film’s most iconic and influential moments is the “Akira slide”—the flawless and stylish maneuver where Kaneda slides his motorcycle to a perfect stop amidst a high-speed chase. This scene has become emblematic not only of Akira’s kinetic energy and visual prowess but also of the potential for animation to convey dynamic motion with a sense of weight, style, and personality. The technique has been endlessly referenced and homaged in both anime and live-action works worldwide, shaping how filmmakers portray fast-paced chase and action scenes. Its balance of fluid animation, camera angles, and character flair set a new benchmark for kinetic storytelling, inspiring generations of animators and directors to capture similar moments of cool, precise motion.

Moreover, Akira’s soundtrack and sound design contribute significantly to its gritty and intense atmosphere, reinforcing the emotional beats and tension throughout the film. The score blends pulsating electronic music with haunting melodies, capturing the film’s blend of futuristic dread and human vulnerability.

Critically, Akira is celebrated not just for its technical achievements but also for its complex storytelling and thematic depth. It does not offer neat resolutions or clear heroes; instead, it portrays a morally ambiguous world where power is both destructive and transformative. The lack of easy answers enhances its emotional and intellectual resonance, making it a powerful narrative of destruction, evolution, and hope.

Akira stands among the most influential works in animation and film, a piece that’s carved its place indelibly in cultural history. Its influence isn’t just in the stunning visuals or the groundbreaking animation techniques; it’s also in how it expanded the horizons of what anime could achieve on a global scale. Otomo’s dystopian vision challenged viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about power, chaos, and societal resilience. Years after its debut, the film continues to inspire and provoke new generations of creators—each eager to capture some fragment of its raw energy and layered storytelling. Akira’s legacy is not just that of a cinematic masterpiece but as a catalyst that reshaped the possibilities for animated storytelling, making it a timeless beacon for artists and audiences alike.