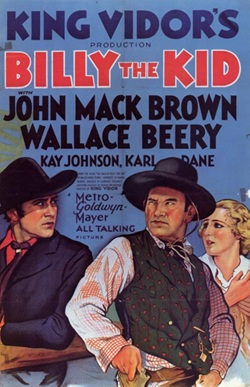

In a frontier town, land baron William P. Donavon (James A. Marcus) finds his control challenged by the arrival of a English cattleman named John W. Tunston (Wyndham Standing). Donavon orders his henchmen to gun down Tunston on the same day that Tunston was to marry the lovely Claire (Kay Johnson). Tunston’s employee, an earnest young man named Billy The Kid (Johnny Mack Brown), sets out to avenge Tunston’s murder. When Billy starts killing Donavon’s henchmen, it falls to Deputy Sheriff Pat Garrett (Wallace Beery) to arrest him. When Billy escape from jail and rides off to be with Claire, Garrett pursues him. Garrett is a friend of Billy’s and he knows that Billy’s killings were justified. But he’s also a man of the law. Will he be able to arrest or, if he has to be, even kill Billy? Or will Garrett let his friend escape?

In a frontier town, land baron William P. Donavon (James A. Marcus) finds his control challenged by the arrival of a English cattleman named John W. Tunston (Wyndham Standing). Donavon orders his henchmen to gun down Tunston on the same day that Tunston was to marry the lovely Claire (Kay Johnson). Tunston’s employee, an earnest young man named Billy The Kid (Johnny Mack Brown), sets out to avenge Tunston’s murder. When Billy starts killing Donavon’s henchmen, it falls to Deputy Sheriff Pat Garrett (Wallace Beery) to arrest him. When Billy escape from jail and rides off to be with Claire, Garrett pursues him. Garrett is a friend of Billy’s and he knows that Billy’s killings were justified. But he’s also a man of the law. Will he be able to arrest or, if he has to be, even kill Billy? Or will Garrett let his friend escape?

There were two silent biopics made about Billy the Kid but neither of them are around anymore. This sound movie, directed by King Vidor, appears to the earliest surviving Billy the Kid film. It’s a loose retelling of Billy’s life and his friendship with Pat Garrett and it doesn’t bother with sticking close to the established facts but that’s to be expected. It’s an early sound film and, seen today, the action and some of the acting feels creaky. Wallace Beery was miscast as Pat Garrett but I did like Johnny Mack Brown’s performance as the callow Billy. The movie goes out of its way to justify Billy’s murders and it helps that Billy is played by the fresh-faced Brown. King Vidor shows a good eye for western landscapes, a skill that would come in handy when he directed Duel In The Sun seventeen years later.

There are better westerns but, for fans of the genre, this film is important as the earliest surviving film about one of the most iconic outlaws not named Jesse James. It’s interesting to see Brown, usually cast as the clean-cut hero, playing a killer here. The film’s ending is pure fantasy but I bet audiences loved it.