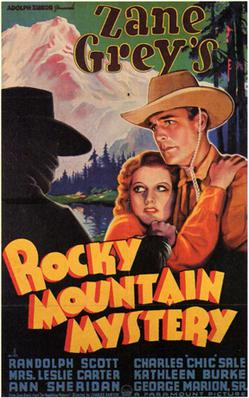

Larry Sutton (Randolph Scott) is an engineer who has been sent to take over operations at a radium mine that is owned by the Ballard family. Previously, Larry’s bother-in-law was in charge of the mine but he has disappeared and is suspected of having murdered the foreman at the Ballard Ranch. With Jim Ballard (George F. Marion) on his deathbed and being cared for by the foreman’s wife (Caroline Dudley, credited as Mrs. Leslie Carter), Ballard’s nieces (Ann Sheridan and Kathleen Burke) and nephew (Howard Wilson) have come to the ranch to find out about their inheritance.

Larry Sutton (Randolph Scott) is an engineer who has been sent to take over operations at a radium mine that is owned by the Ballard family. Previously, Larry’s bother-in-law was in charge of the mine but he has disappeared and is suspected of having murdered the foreman at the Ballard Ranch. With Jim Ballard (George F. Marion) on his deathbed and being cared for by the foreman’s wife (Caroline Dudley, credited as Mrs. Leslie Carter), Ballard’s nieces (Ann Sheridan and Kathleen Burke) and nephew (Howard Wilson) have come to the ranch to find out about their inheritance.

Soon, a cloaked figure starts to murder Ballard’s heirs, one-by-one. Working with eccentric Deputy Sheriff Tex Murdock (Chic Sale), Larry tries to discover the identity of the killer and keep the mine from falling into the wrong hands.

Rocky Mountain Mystery is unique in that it is a Randolph Scott western that takes place in what was then modern times. Even though both Larry and Tex prefer to ride horses, the murderer tries to escape in a car, people use phones, and the entire plot revolves around a radium mine. The film mixes the usual western tropes of grim heroes, eccentric lawmen, and valley shoot-outs with a dark mystery that actually holds your attention while you’re watching the film. Always ideally cast in these type of films, Randolph Scott is both tough and intelligent as Larry Sutton. He may be a cowboy but he’s a detective too. Scott gets good support from a cast of familiar faces. Ann Sheridan is especially good as the niece who knows how to handle a rifle.

These B-westerns can be a mixed bag but Rocky Mountain Mystery held my attention with a plot that was actually interesting and a strong performance from Randolph Scott. Watch it and see if you can guess who the identity of the Ballard Ranch murderer.