In the days after World War I, a man (Paul Muni) stumbles out of an apartment building and then walks down to the local police station. He informs the officer on duty that he just shot a man. He refuses to explain why he shot the man and, when asked for his name, he identifies himself as James Dyke. The office notices a poster for “Dyke & Co.” on the wall and realizes that the man made up his name. The man is convicted and sentenced to be executed.

The years pass as the man waits for his execution date. He is a model prisoner, working hard in the garden and writing editorials for the newspapers in which he warns young readers about pursuing a life of crime. The money he makes, he puts into Liberty Bonds. He continues to refuse to tell anyone his first name.

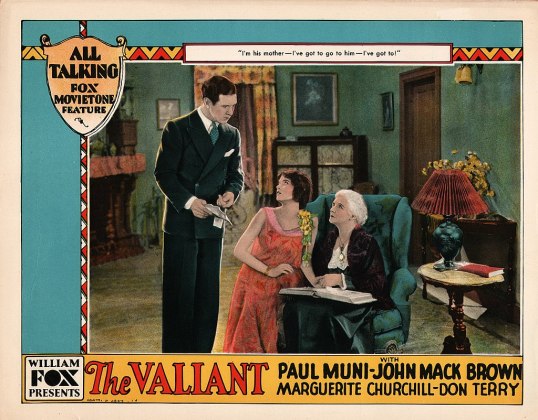

In a small town, an old woman (Edith Yorke) sits in her rocking chair and has visions of all the men who went to war and never returned. When the woman sees a picture of James Dyke in a newspaper, she thinks that he looks like her son, Joe, who long ago went missing. The woman’s daughter, Mary (Marguerite Churhill), realizes that her mother is planning to make the trip to the prison to see him before he is executed. Mary decides to go herself. She tells her fiancé (John Mack Brown) that she could never get married if it turned out her brother was a murderer. Meanwhile, the old woman continues to have visions of soldiers marching to war.

At the prison, James Dyke tells Mary that he has no family and he has no past. But he did serve in World War I and during that time, he met her brother and he saw him die heroically in battle. Dyke tells her to write to the army for the details of her brother’s death but to be aware that they might not even know whether or not he actually served because the war was such a confusing time that “they don’t know what happened to half the men out there.” Dyke and Mary continue to talk as the hour of execution draws near….

An adaptation of a one-act play, The Valiant was released in 1929, at a time when America was still coming to terms with the horror of the Great War and Hollywood was still trying to adjust to the arrival of sound. Though many had assumed that sound films would just be a fad, it turned out that audiences really did like to hear the dialogue as opposed to just reading it. The Valiant is the type of melodrama that was popular during the silent era and the film does feature title cards that appear between scenes. “A city street — where laughter and tragedy rub elbows,” one card reads. Another one announces, “Civilization demands its toll.” At the same time, it is a sound picture. The first five minutes of the film are just the Man walking through the city and listening to the sound of cars honking and people talking. Like many of the early sounds films, it’s obvious that the majority of the cast was not quite sure how they should handle delivering their dialogue. Some people talk too loudly. Some talk too softly. Quite a few deliver their dialogue stiffly and without emotion. Others use way too much emotion.

The only actor who seems to be fully confident in his ability to perform with sound is Paul Muni, making his screen debut in the lead role. Muni gives a strong and empathetic performance, one that makes even the most melodramatic of dialogue feel naturalistic. Muni shows an instinctive knowledge of how to deliver his lines with emotion without going over the top, which was a skill that many of the actors who tried to make the transition to sounds films never learned. Paul Muni was the first great actor of the sound era, as well as one of the first screen actors to use what would eventually become known as the Method. Among the actors who were directly inspired by Muni were John Garfield, Montgomery Clift, and Marlon Brando. Much of modern acting owes a huge debt to the work of Paul Muni.

Seen today, the contrast between Paul Muni’s performance and the film’s staginess can make The Valiant seem like a rather surreal film. While Muni captures the screen and confidently delivers his lines, everyone else seems hesitant and unsure of how to reply. The end result is that, to modern audiences, The Valiant can almost seem like a filmed dream. From the shot of Muni walking down the noisy city street to the sudden appearance of a swing band playing in the prison cafeteria, the film can seem almost Lynchian in its oddness.

The Valiant was a box office success and, according to the notes in the Academy archives, Paul Muni was among the actors considered for the second Best Actor Oscar. (That year, there were no official nominations and only the winners were announced.) The Oscar went to Warner Baxter for In Old Arizona but Muni would go on to have an amazing career.