The great director Federico Fellini was born, on this day, 125 years ago.

He was born in Rimini. That’s in Northern Italy. (The Italian side of my family comes from Southern Italy and yes, there is a difference.) Fellini was 19 years old when he enrolled in law school but records, which were admittedly spotty at the time, seem to indicate that he never attended a single class. Instead, Fellini found work as a writer, working first as a journalist and then a screenwriter. (He was one of the many credited for writing the screenplay for Rome, Open City.) He began his directing career as a neorealist in the 50s but soon crafted his own unique style, one which openly mixed humor with drama and fantasy with earthiness. Fellini established himself as one of the world’s best directors, a filmmaker who made art films that not only entertained but also provoked thought. Fellini was a director who embraced life’s contradictions as well as being a strong anti-authoritarian who rarely commented on politics but did make known his distaste for communism. He was also one of Mario Bava’s best friends.

My favorite Fellini film is 1960’s La Dolce Vita.

Ah, to be rich, decadent, and jaded in Rome in the early 60s! Or maybe not. Sometimes, being jaded is not as much fun as it seems.

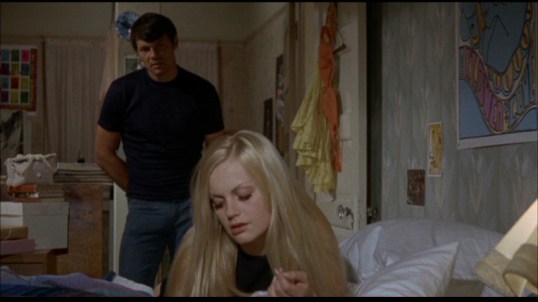

La Dolce Vita is largely remembered for the scene in which actress Sylvia (Anita Ekberg) and journalist Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) wade into Rome’s Trevi Fountain. While that it is a great and sensual scene and justifiably famous (and, in fact, the film’s poster was originally a shot of Ekberg in the fountain despite the fact that the scene is only a small part of a 3-hour movie), it’s often overlooked that the scene itself does not have a happy ending. When Marcello and Sylvia return to Sylvia’s hotel, Sylvia is slapped by her loutish boyfriend (played by Lex Barker). Marcello, meanwhile, has a fiancée named Emma (Yvonne Furneaux) who is recovering from a recent overdose. Even though Marcello swears that he loves Emma and that he would do anything for her, he is still compulsively unfaithful.

When we first meet Marcello, he’s in a news helicopter, watching as a statue of Jesus is flown over Rome. However, Marcello is distracted by the sight of a group of women sunbathing on a nearby rooftop and he tries to get their phone numbers before returning to following the statue. That pretty much sets the tone for most of what we see of Marcello over the course of La Dolce Vita. He’s searching for the profound and transcendent but he frequently gets distracted by his own more earthy desires.

The film follows Marcello as he encounters different people in Rome and the surrounding area. Some of them are rich and some of them are poor. All of them are looking for something but none of them seem to be quite sure what it is. A possible sighting of the Madonna brings a crowd of people to the outskirts of Rome, where everyone asks for something but the end result is only chaos. A meeting with an intellectual friend of Marcello seems to offer a solution to Marcello’s ennui until a tragedy reveals that his friend was even more lost than Marcello. (The film’s sudden tragic turn took me very much by surprise when I first saw it, despite the fact that countless filmmakers have imitated the moment since.) A possibly important conversation on a beach is made unintelligible by the crashing waves and, instead of providing enlightenment, it ends with a shrugs and an enigmatic smile. There’s a definite strain melancholy running through the film though there’s also a certain joi de vivre to many of Marcello’s adventures. Marcello is torn between seeking transcendence and seeking pleasure. Fellini shows us that both are equally important. It’s left to use to decide whether the pleasure is worth the heartache and vice versa.

La Dolce Vita is visually stunning portrait of life in Rome at a very particular cultural moment. Marcello Mastroianni is the epitome of decadent cool in the lead role but he’s also a good enough actor to let us see that Marcello is never quite as proud of himself or as happt with his life as everyone assumes he is. La Dolce Vita may be about a specific cultural moment but, as a film, it is timeless.