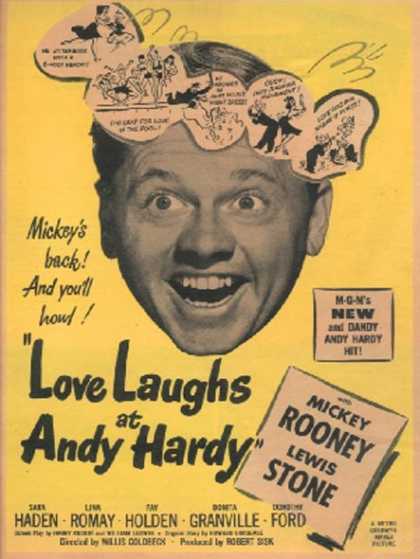

I cringed a little when I saw that the 45th film in Mill Creek’s Fabulous Forties box set was 1946’s Love Laughs At Andy Hardy.

This was because I had never seen an Andy Hardy film before but I did know enough to know that, starting in the 1930s, MGM made a series of films that featured Mickey Rooney in the role of a “nice, young man” named Andy Hardy. Andy was a well-meaning kid who grew up in Middle America under the watchful eye of his father, Judge Hardy (Lewis Stone). What little I had heard of the Andy Hardy films led me to suspect that they were very much a product of their time and had not aged particularly well.

Having now watched Love Laughs At Andy Hardy … well, I can confirm that it is a product of its time. And it is definitely an uneven film, though perhaps I would have felt differently if I had seen any of the other Andy Hardy films. (Love Laughs was the 15th film about Andy Hardy and it pretty much assumes that the viewer already knows who Andy and all of his friends and family are.) But I will say this: Mickey Rooney was a really good actor. In fact, as I watched Love Laughs At Andy Hardy, I was shocked by just how good a performance Rooney gave. When I think of Mickey Rooney — well, to be honest, it’s rare that I ever do. But when I do, it’s usually in relation to the exploitation films he made after he was a star. These were movies like The Manipulator or Silent Night Deadly Night 5, all of which feature an elderly and obviously unwell Mickey acting up a storm. In contrast to those film, in Love Laughs At Andy Hardy, Mickey gives a totally empathetic and, at times, even subtle performance. Even by contemporary standards, his performance feels real and, as I watched, I started to understand how there actually could have been 16 separate films about Andy Hardy. You really do find yourself caring about the little guy,

As for this film, it opens with Andy returning from serving in World War II. Apparently, he left college to enlist in the army. Now that he’s back in America, he’s ready to return to college and ask his old girlfriend, Kay (Bonita Granville) to marry him. However, to Andy’s shock and disappointment, Kay has moved on and has other plans. Why, it’s almost enough to make Andy want to drop out of school, give up his dreams of becoming an attorney, and try to find work as an engineer in South America!

Fortunately, Judge Hardy is there to talk some sense into his son.

It’s all fairly predictable and, as I said before, definitely uneven. I get the feeling that a lot of the scenes in Love Laughs At Andy Hardy were meant to serve as call backs to previous films in the series. Watching this film without a context can lead to a lot of confusion. But, again, it’s all saved by Mickey Rooney’s performance. While I can’t really give this film a strong recommendation, I imagine if you’re fan of Rooney’s or the Andy Hardy films, you’ll enjoy it.

Perhaps the best scene in the film comes when Andy is set up on a blind date with a girl named Coffy (Dorothy Ford). When Andy goes to Coffy’s dorm to pick her up, he can’t understand why all the other girls keep looking at him and laughing. However, once Coffy shows up, it quickly becomes obvious. Coffy is 6’2 while Andy is a full foot shorter.

However, when Andy and Coffy arrive at the college dance, they defy all the laughs and the snide remarks. Instead of surrendering to the expectations of snarky society, they perform a dance to end all dances and I’m going to conclude this review by sharing it below.

Enjoy!